There is nothing like a visit to Bed, Bath and Beyond to restore one’s confidence in American ingenuity. I’m not talking about the whiz bang intelligence required to send a man to Mars, invent the Internet, or thwart Russian hackers. I’m talking about the everyday can-do spirit of ordinary Americans who tinker in their kitchens and garages to devise a better way to make it through the day

These humble inventors live in obscurity. I imagine them fiddling with a spatula or whisk, muttering their mantra, “Some men see things as they are, and ask why. I dream of things that never were, and ask why not?”

The fruits of their labor are on display at Bed, Bath and Beyond, a dizzying collection of specialty spoons, spatulas, scoopers, slicers and dicers, each exquisitely designed to fill a sliver of a niche.

The 1950s saw an explosion of kitchen appliances, all intended to improve the life of the homemaker. These innovations represented low-hanging fruit. The demand for a clothes dryer was obvious. This was an era when it wasn’t yet a cliché for a husband to give his wife an appliance as an anniversary present, perhaps a new-fangled toaster that toasted both sides simultaneously, or a garbage can with a foot pedal to open the lid, leaving both hands free to scrape a plate.

Lillian Moller Gilbreth, born in 1878, is known as the “First Lady of Engineering,” an industrial psychologist and efficiency expert, who studied housewives to identify the most efficient approach to kitchen chores.[1] It was Lillian who invented the garbage can with a foot pedal in 1920. Her other standouts included shelves on the fridge doors, such as a butter tray and egg keeper. Yes, “why not” indeed.

The current generation of gadgeteers face a crowded landscape, and only the most enterprising can identify and exploit an empty niche. The recent movie Joy profiled the entrepreneur Joy Mangano who made a fortune with a self-wringing Miracle Mop, designed so you don’t have to touch that wet dirty thing. The movie closes with Joy interviewing a young couple who are seeking their fortune with their ergonomically designed lint roller.

If you want to see where dreams can still come true, go to Bed Bath and Beyond.

The following are the most intriguing items I harvested on a recent stroll through the store.

But I warn you. You will also confront the silly excesses of our culture. I think of the millions who make do with a single dinged up bowl and a combination knife/machete. They must be astonished Americans are so pressed for time that they need a special device to crush garlic cloves, that they are so consumed with presentation they need a special serrated knife to keep the cut edge of lettuce from turning brown, that they have no concept of portions given the plethora of storage containers and that they have unlimited storage space for all this inventive crap.

1. Measuring cups marked on the inside

My existing Pyrex measuring cups, which have served me well for over 30 years, require me to either bend over to see the volume markers or lift the cup to eye level. I have meekly accepted this annoyance, but an enterprising housewife banged her fist on the counter and said, “NO MORE!! Let’s Keep America Great and spare ourselves the agony of Making America Great Again!”

These angled measuring cups allow me to look down into the cup. No bending or lifting required.

The elimination of bending is a general theme in kitchen gadgets, starting with the aforementioned step-pedal garbage can, followed by the bendable straw patented by Joseph Friedman in 1937. I grew up with the humble dust pan, but now I have a long-handled one. I don’t need to bend over anymore. I gratefully stand on the shoulders of those who came before me.

2. Angry Mama Microwave Cleaner

My pet peeve is not the grease-spattered microwave, it’s dishes left in the sink, particularly when encrusted with old egg yolks, but I do appreciate the strategy of targeting frustrated housewives. The steaming mad character captures the mood, but Angry Mama execution does present conceptual problems. First you have to rip off the Mama’s hair and then her head in order to fill the body with vinegar and water, which comes across as an act of vengeance. Then you twirl Mama in the microwave until a vinegar steam bath erupts from the vents in her head. The package notes that after the steam bath, you have to wipe down the microwave, then clean the woman, so Angry Mama is not a time saver.

I bought the woman to celebrate its creativity, however misguided, but returned it the next day. In my disorganized hands, the parts would certainly become separated. I didn’t want a decapitated head rolling around my “things accumulate” drawer.

2. Scissors-cutting board combination

Chopping carrots has always been a two-step process – first the cutting and then the nano-second time-suck of transferring the carrots from the cutting board to the bowl. The obvious solution – combine the two by attaching a miniature cutting board to the lower blade of the scissors.

I bought one but always forget to use it. It takes me more time to find the scissors than use a standard-issue cutting board. Scissors come in many styles, including one with multiple blades that can mince herbs with one cut. Over a course of a year, a nano-second here and there might add up to a full second of saved time.

4. Collapsible whisk

Oh, the clutter of bulky whisks! Such an annoyance, particularly when the bulbous whisk jams the drawer that resists all jiggling and jimmying. I applaud the inventive mind who realized this is no way to live and then did something about it! I hold the nifty flat whisk in my hand, twist the base and marvel as the head elegantly blossoms and clicks into its full-bodied splendor.

5. Egglettes

Egglettes address the nightmare of hardboiled eggs that refuse to peal. Just crack the eggs in the little plastic containers then boil them. Genius.

However, the bigger question is why some eggs peal like a dream, while others leave you with a flea-bitten egg that is hardly worth eating.

The answer is related to the anatomy and chemistry of the egg. I’m sure you’ve noticed the membrane that separates the egg white from the shell. This keeps the sticky and acidic proteins in the egg white from glomming onto the shell and making it impossible to peel. You can guess where I’m going here. It’s all about the membrane, the difference between success and failure. Is that flimsy membrane stalwart enough for the job?

Here’s the kicker – the fresher the egg, the lower the pH of the egg white and the stickier it becomes. The membrane is overwhelmed. Old eggs don’t have this problem

Egglettes are the clever work-around. Hard boil the egg outside the shell.

I love this product. It provides an ingenious and time-saving solution to a truly annoying problem. I hope the inventor makes a fortune, but I didn’t buy any Egglettes. They would take up too much room. I’m waiting for the next-gen, collapsible Egglette. Besides, there’s and easy work-around. Problem solved if you let your eggs languish in the fridge for a few days.

6. Hydralight Flashlight  The Hydralight makes the list as a cautionary tale illustrating the hyperbolic advertising that accompanies gadgets.

The Hydralight makes the list as a cautionary tale illustrating the hyperbolic advertising that accompanies gadgets.

I responded to the claim that the flashlight “runs on water,” and “no batteries needed.” Here, midst the maze of Bed Bath and Beyond, I was privy to the fruits of another inventive tinkerer who had tapped into the energy potential of good old H2O. I looked around to make sure that I hadn’t stumbled into the thermodynamic or cold fusion aisle of the store, but no, the aisle was devoted to other “As Seen on TV” items.

I bought a Hydralight, excited about the prospect of living in a world without the crushing disappointment of a flashlight with dead batteries.

On closer inspection, which required a magnifying glass, I saw the “Runs on Water” claim came with an asterisk. The faint print on the back of the package noted that water was not the energy source, but merely activates the “fuel cell.” I was in the presence of champion dissembling! In smaller, fainter print the package made a clever distinction between a battery and a fuel cell. Specifically, “a battery makes energy stored exclusively inside the battery. A fuel cell requires external elements, such as water.” Rocket scientists may embrace this distinction, but for the pedestrian flashlight, the subtleties of a battery vs. fuel cell are irrelevant.

Chastened, I returned the Hydralight the next day.

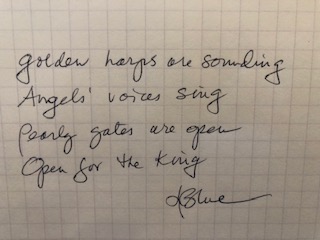

The missing words in the following poem are a collection of anagrams, i.e. words that share the same letters like spot, post, stop, etc. The number of asterisks indicates the number of letters in the word. One missing word will rhyme with either the previous or following line, giving you a big hint. Your job is to solve the missing words based on the above rules and the context of the poem. Scroll down for the answers.

In the American kitchen, not one convenience should be ******,

Time saving gadgets are a particular point of pride.

******, time spent bending over is time that is lost,

So my purchase of a special measuring cup is well worth the cost.

However, gadgets have accumulated and without even knowing.

* ***** ended up with drawers and shelves, cluttered and overflowing.

[1] Lillian Gilbreth (1878-1972) is a trail blazer on many fronts, one of the first women to get a PhD in engineering and psychology. She was a full partner with her husband Frank in their engineering and consulting firm. The two had twelve children together, and the children participated in many of their efficiency studies. The novel Cheaper by the Dozen, written by two of their children, is based on their well-organized home life.

Follow Liza Blue on:

Share: