John was pleased that the woman sat next to him on the commuter train, even though it was the only open seat. She could have stood in the vestibule, he thought. The next day there was a vacant seat. She wasn’t forced to sit next to him, but she did. John trembled, his pulse quickened, and he sat up straight. Nobody had ever made an explicit choice to sit next to him. He knew why.

He was ugly, a brutal

combination of the worst features of his parents – large bulging eyes and sloping

chin that barely accommodated a mouth.

His long gangly legs and arms gave him a peculiar gait. Even as a kid, he sensed that people startled

at his appearance. Besides his mother told him as much.

“Your father was not a

handsome man, but he made up for it with his smarts. You look him. You walk like him. But you’re smart

like him. You’ll be fine. You know that men are the ones who

choose, women are chosen. Your sister is the one who needs help.”

Over the years, any

extra money was devoted to tinkering with his sister Gloria – a nose job, a

chin implant for sure, and probably other adjustments done on the sly.

John accepted his appearance and considered himself luckier than his classmate

Lucy, who had a horrible stutter, or that kid a couple grades below with a

withered arm. Besides, he always made the honor roll. His mother

was right. He’d be fine, and he could

see that Gloria, who was a such a poor student, needed some upgrades.

The next day on his way

home from work, John waited on the platform as the commuters streamed onto the

train. He saw the woman approach and also noticed others turning their

heads to look at her. He supposed they were looking at her tall thin

figure, her glistening black hair, and long legs. The woman looked

directly at him and motioned for John to follow and sit next to her.

John never expected

that any woman would seek him out. The thought of dating and marriage

held no interest for him. Every birthday, Gloria teased him by asking if

he was a “leg man or a breast man.” He always said he was a breast man

since magazines and movies suggested that this was the key attribute. In

reality he had no idea what she was talking about.

Her intense stare

confused him. He was most accustomed to people quickly glancing and moving

away. He reflexively touched his nose and chin to make sure he was the

same person. He knew his mouth had a way of sagging down into a grimace,

so he tightened up his cheeks.

“I can’t believe we

keep bumping into each other,” she said. “We get off at the same station,

don’t we?”

John sat dumbstruck, staring into his newspaper, unable to fill the uncomfortable silence. As the train shuddered forward, her shoulder briefly touched his, and one foot brushed his calf. John swallowed hard and stared out the window. The crossword puzzle lay untouched on his lap.

Over the next week, she sat next to him every day. John switched his seats around, sometimes in the back, sometimes in the front, and even in the upper tier, the last place anyone wanted to sit. She always found him, so he knew that she was seeking him out. She began to sit closer to him so that their thighs touched when the train lurched. Perhaps he felt a flicker of a spark.

He summoned the courage to say the first

words.

“Hello, I’m John

Dawes.” His voice rasped from disuse.

“I’m Cecilia.

I’ve noticed that you like crossword puzzles. Shall we work on them

together?”

They started to save

the morning crossword to work on in the evening as the train inched into the

suburbs. To impress Cecilia, he bought two copies of the paper so that he

could practice during his lunch hour. It worked. She expressed amazement at

his grasp of word play.

Cecilia’s interest remained mysterious, but

now John thrilled to her touch. He didn’t question it. One

night as they pulled into their destination, Cecilia asked if he wanted to grab

a drink at the corner pub. John could only nod.

The dim light in the bar

bolstered his confidence. They exchanged basic pleasantries. She

was a biologist at the Natural History Museum, he worked in the IT department

of a financial services company. Her apartment was a couple blocks

away. When she asked where he lived, he stammered that he had a house

twenty minutes away.

“Wow, you got your own

home. Must be doing well. That’s a pricy area. I could barely

afford to rent a one bedroom. Good for you.”

John changed the

subject to the weather. He didn’t want to confess that he lived in his

childhood home. He had no idea of what Cecilia thought of him, but at age 27 he

did know that living with your mother and sister was not an asset. They

settled into a comfortable routine sitting next to each other on the train,

then going to the bar for a beer.

John began to arrive

home late for the dinner. His mother stood in the doorway, wearing her

apron, hands on hips, flummoxed by his new schedule, disrupting her precise

schedule of dinners.

“Call me when you work

late. Your dinner’s cold.”

“Mom, I’m sorry. I met a

friend on the train, and we go out for a drink.”

“A friend you met on

the train? Why don’t you bring him home for dinner? I never meet

your friends.”

“It’s a girl, I mean a

woman, a female.”

“A girlfriend?

It’s about time. Oh, thank God.” She clasped her hands in prayer

across her ample breasts, leaned back and yelled for his sister. “Gloria, guess what, our Johnny finally has a

girlfriend.”

The bathroom door

slammed open, and Gloria came bustling into the kitchen tying up her bathrobe,

her hair flecked with suds from her interrupted shower. “Who is she, what

does she look like, where does she work, has she been married before, does she

have children, does she want children?”

“She’s not a

girlfriend, she’s a girl who is just a friend. We sit around and

talk.”

“A friend who’s a

girl? What the hell is that?” asked his mother.

“Mom, it means Johnny’s

not having sex or anything. Right Johnny?”

He nodded, and

wondered, not for the first time, why sex had to be so important. He only

wanted companionship from Cecilia, but the last time on the train, she put her

head on his shoulder. Her other touches could be construed as the result

of random lurches in the train. When they worked together on the

crossword, their thighs were plastered together along their entire length, but

you couldn’t share the crossword without sitting close together, could

you? But Cecilia’s head on his shoulder was so deliberate that John was

sure she wanted more.

“Well at least it’s a

start, ’bout time.” Gloria turned and tromped back to the bathroom.

The next day at the bar

Cecilia said, “Hey why don’t we order dinner. Let’s split a burger.”

His mother was pacing

in the kitchen when he got home. “What’s going on? I cook for you

and now it goes untouched. Bring your friend here for

dinner.”

At the bar, he’d

noticed other diners looking at him, probably wondering, just like him, how

such an ugly man could attract such a woman. He reveled in those

moments. He imagined people were thinking, “he must be a really

interesting guy, there’s no other reason she’d be sitting with him.” Even

so, he kept putting his mother off. He couldn’t bear the thought of her

peppering Cecilia with questions about marriage and children.

“A friend who is a

girl,” she sputtered, “never heard of such a thing. It’s time you thought

about starting a family. You’re smart. You’ve got a good job.

What more could a girl want? That was enough for me.”

Over the next week, John

and Cecilia worked their way through the bar menu, often sharing an appetizer

and an entrée. They talked of their ambitions. She wanted to go

back to school and get a PhD in biology, he wanted to start his own IT

consulting business but didn’t know how.

“Oh, I can help you

with that,” she said, “We’d make a good team.”

This must be another

sign of a relationship, thought John, indisputably confirmed when she squeezed

his thigh.

“Let’s go back to my

place, finish the evening with some wine? Okay with you?”

He flushed as Cecilia

cradled her hand in his. She moved in closer, her lips brushing his

cheek. “What the hell,” he thought. “I might as well give it a

try.” He had no idea what might come next but felt his slight flicker of

a flame burn brighter. He was willing to be surprised.

“Hear that sound?” she

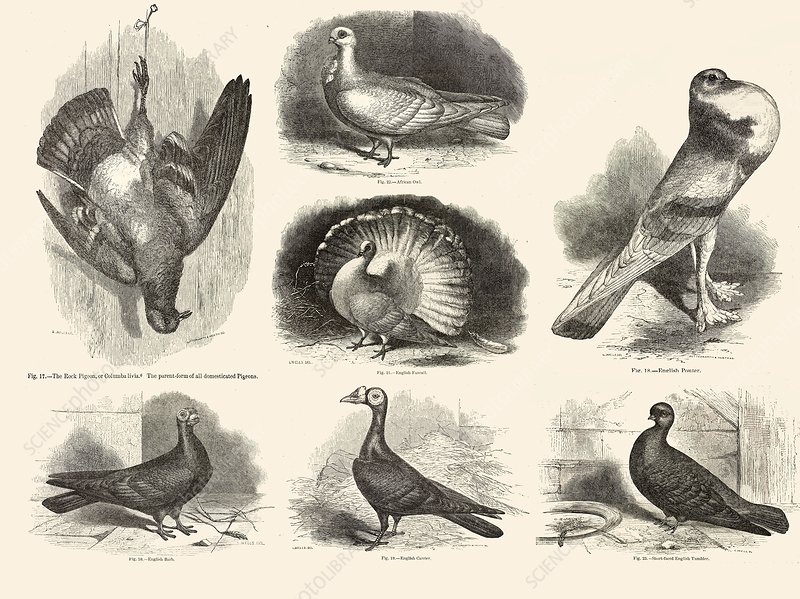

asked as they walked along. “That’s Brood XIII of the 17-year

cicadas. Have you ever lived through a cicada

summer?”

He shook his head and

let her keep talking. “The nymphs emerge from the ground after a 17-year

hibernation. They quickly molt into

adults that crawl up the trees and mate. Nobody knows why the cycle is 17

years exactly and how they keep track of time, but you’ll see, in a couple of

weeks, there’ll be millions coating the trees. After they mate, they die

and fall to the ground. They crunch when you step on them.

Here’s my apartment. Come on up.”

She led him through the

small kitchen and living room and out onto her balcony. “This is my

second cicada summer here. I was about 12 years old for the first one, so

I couldn’t take full advantage. Now, I figure I’ve got three or four

Brood XIII’s left in my lifetime, got to make each one count. This is a

biologist’s dream. Do you hear that thrumming noise? It’s just

starting. That’s the sound of pure

sexual energy. It will last a month a

more. This will be an exciting month.”

As he strained to hear

the noise, she stroked his arm, clasped her leg around his, unbuttoned his

shirt and pulled his head down for a probing kiss. She led him into the

bedroom, ripped off his clothes, climbed on top and took over. He was pleased his anatomy functioned, but

beyond that he was unimpressed, confused as to why people made such a fuss

about sex. Cecilia climbed back on top. By the third time that night his flickering

flame had erupted into a blazing torch. He joyously succumbed to the

ancient forces of lust and blind passion.

The two became

inseparable. Cecilia constantly called him at work and sometimes showed

up unannounced. Once she insisted that they take a long walk in the woods

where they joined the cicadas in their sexual orgy. When he returned to

work several hours later, he basked in the knowing looks from his colleagues. One leaned over his cubicle to pluck crushed

leaves from his sweater. And then his hair.

He abandoned his usual

summer wardrobe of short sleeved shirts.

Long sleeves were required to hide the bitemarks on his arms. His work

colleagues commented on his odd choice of turtlenecks in the middle of summer,

but he needed something to cover his vivid array of ripening bruises. The bathroom became the venue for their most

acrobatic performances. Some were

frightening. Cecilia liked John to

struggle and thrash his way out of her tenacious embrace. One time he staggered backward and smacked

his head on the sink. The tender knot

lasted for more than a week. He didn’t

care. Fear transformed his pleasure to rapture.

One evening they went

to an outdoor symphony concert. The lawn was deserted; nobody wanted to

sit among the cicadas. Their thrumming drowned out the music.

Cecilia was delighted by the sparse crowd and spread her blanket beneath the

coated branches of a maple tree.

“Don’t move” she said.

“I can feel them coming up underneath us.” She was right, the blanket

burbled and quivered as the seething mass of nymphs emerged.

She peeled back the

corner of the blanket to look for the exit holes as they struggled to the

surface. “Look at this one, it’s halfway through its molt.” She

used her long fingernail to peel the covering off the emerging adult.

Once the cicada spread its wings, she tenderly carried it over to the tree

trunk and reached up as high as she could.

“John, can you help me

give this cicada a boost? Help him get started farther up. He needs

to get moving if he wants to mate. He’s

only got a couple of weeks left.” John held the cicada gingerly between

his thumb and index finger as he looked into their bulging red eyes. He struggled to appreciate the creepy and

prehistoric beauty that so inspired Cecilia.

Cecilia’s interest in

cicadas intensified as the thrumming reached its peak. She started every

day by playing a recording of the landscape service mowing the parkway. The cicadas mistook this sound as a mating

call and were attracted to Cecilia’s outstretched arms. Dozens landed on her arms as she played the

recording in a continuous loop.

John didn’t share her

enthusiasm for cicadas, but he feigned interest to make her happy. It wasn’t hard. All he had to do was

smile and nod when she talked about cicadas.

Moments later they would be breathlessly pawing each other. She

didn’t talk about anything else and she talked constantly.

John told his family

he’d found his own apartment, though he suspected his mother knew he was living

with Cecilia. She began to call him every day, insisting that she be

introduced to his new friend. He knew a meeting was inevitable, but Cecilia

kept putting him off. “You’re all I want. I’m not ready to

share you.”

Finally, he got her to

agree to a luncheon. Cecilia insisted on a restaurant that had a large

patio beneath overarching elms.

“Do you really want to

sit outside under the trees? The cicadas are so deafening my mother won’t

be able to hear.”

“But they’re beautiful

and we won’t have another chance for 17 years,” she said.

His mother’s and

sister’s eyes widened when he introduced her. He wasn’t surprised, he had

come to appreciate Cecilia’s cropped shirts and taut skirts. John just

wished she hadn’t kept stroking his leg while she prattled on about cicadas –

the significance that the 17-year cycle was a prime number, the total weight of

dead cicadas accumulating around them, and the sounds they made.

“It’s hard to notice

but they make two different sounds,” said Cecilia. “The male makes that obvious droning noise

with special vibrating organs called tymbals.

With a magnifying glass, I can sometimes see them underneath their wings. The females are harder to hear. They don’t have tymbals, they snap their

wings back and forth. If you listen

closely you can hear this.” Cecilia made

a clicking noise with her tongue. “The

wing clicks signal that the female is receptive. She’s pumped and prime, ready to mate.”

John didn’t like the

direction of this conversation. Cecilia was

poised to give a first-hand account of the pulsating sexual energy the two of

them shared with cicadas. He was relieved when a cicada dropped into her

mother’s soup, distracting Cecilia. Its

delicate legs dimpled the surface of the bisque. Cecilia extracted it,

the golden liquid coating the wings. A pendulous drop hung briefly from

one of the cicada’s wings. It stretched and then fell, splotching her

silk shirt. She didn’t notice.

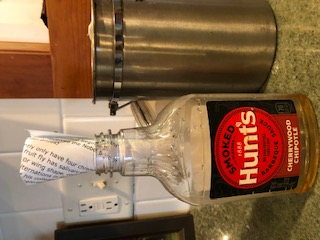

“Isn’t this

lovely? Have you ever seen anything like it?” Cecilia asked, thrusting

the cicada towards John’s horrified mother. “Did John tell you? I’m

collecting cicadas. They’re a terrific source of protein that shouldn’t

be wasted. I put them into my bird

feeder.” She pulled a Tupperware container from her purse and popped the

soggy cicada in.

Another cicada landed

next to Gloria, who shuddered and pushed her chair back. Cecilia picked up

the cicada and balanced it on her arm. “Cicadas don’t bite, they just

suck juice from tree sap. The like to lick the salt off my arm. There’s nothing to be afraid of. Their

little feet tickle. “ Cecilia

giggled. “Give it a try, you’ll like

it.”

John was used to this

behavior, but it had always been just the two of them. Now he realized it

could be off-putting to the less motivated, but he also knew that when

Cecilia launched into cicada stories, he couldn’t stop her, nor did he want

to. He couldn’t wait to get back to their apartment.

Cecilia tried to place

the cicada on Gloria’s arm, but she’d had enough. She pushed her chair

back, “I’m sorry. I’ve gotta leave. Now. It was lovely to meet

you. C’mon Mom, let’s go home.” Cecilia had taken her magnifying glass from her purse and was

staring at the cicada on her arm. She didn’t

notice them leave.

John tried to talk with

her that night. “Cecilia, I’d really I’d like you to get to know my family, it’s

important to me, but it’s hard when you’re so obsessed with these bugs.”

“They’re not bugs, they’re

cicadas. They’re marvelous

creatures. Here help me sort them.”

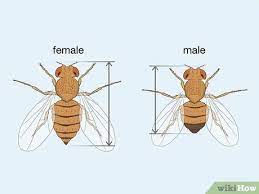

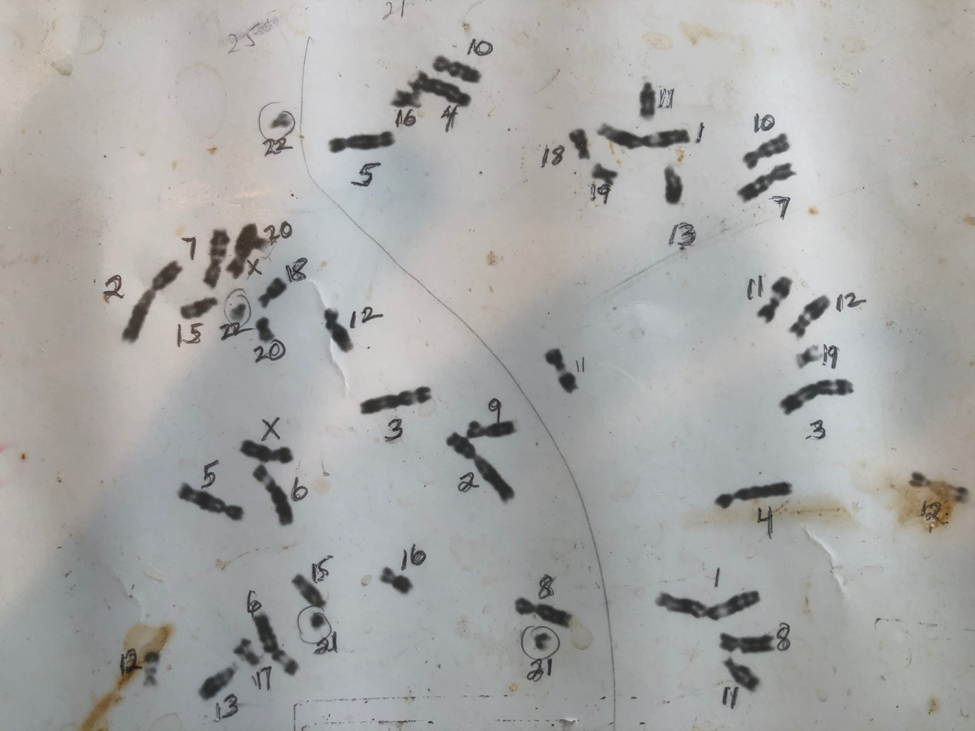

John took the magnifying

glass and examined their genitalia the way she’d taught him. The males with the dome shaped abdomens went

into one bin, the females with the pointed abdomens in the other. “Why do you want to sort them anyway?”

“It’s an

experiment. I want to see if there is an

exact 50:50 ratio of males to females.”

“Why wouldn’t there

be?” Cecilia didn’t answer. “Never mind, but I do need your

attention. Please, can I have just a

moment of your time?” She still hadn’t

looked up. He pressed ahead. “How about another luncheon with my family in

the fall? It would probably be more

relaxing when all this racket dies down.”

“It’s not a racket,

it’s mating. They live underground for

17 years and only see the light of day for about a month and then they die. Don’t you think they deserve their moment in

the sun?”

Cecilia grabbed a

handful of cicadas with one hand, with the other she stroked John’s abdomen and

clicked with her tongue. John knew what

this meant, but he was ready to take a break.

An afternoon of uninterrupted sex had left him raw and bruised. He broke away from Cecilia’s ministrations

and headed to his mother’s house. He

needed to explain Cecilia’s fascination and that the fall would be a better

time to get to know the real Cecilia.

His mother brushed her behavior

aside.

“It’s you I’m worried

about. It’s not the cicada thing, like

you say it’s every 17 years. I’ll be

dead the next time they come back, so it’s not my issue, is it? All I want is to see you happily married. I want you to give me some grandchildren. But is she right girl for you? It’s

that she’s so pretty. Don’t you think you’d be better matched with

someone, I don’t know, someone who…”

“Mom, what are you

saying, that I should try to find someone who shares my same scale of physical

beauty?”

“Yes, that’s it

exactly.”

“I’ve heard what you’ve

said about me, that my eyes stick out, that my scrawny legs make me walk

funny. Your words exactly. But

guess what, Cecilia likes the way I look.

I can’t explain it, but why does it matter? Maybe it’s

pheromones.”

“What are those?”

“I don’t know, it’s an

odor that floats in the air or something, it causes an attraction that can’t be

explained.”

“I don’t smell

anything.”

“That’s just the point,

there’s no explanation. Who cares anyway? You always tell me that

men are the ones that choose. Yeah, so Cecilia chose me first, but I chose

her right after. And here’s something

else. We have sex, a lot of it.”

She flattened her hands

over her ears. “John stop that talk. Right now. We don’t talk

about sex in this house.”

“Guess what else, I’m

really good at it. Maybe that’s what Cecilia finds attractive. You

should be happy for me.”

“Stop, stop. I

can’t be hearing this.” She flustered out of the room before John could

tell her his other revelation, that the combination of sex and fear are

exhilarating, propelling pedestrian pleasure to celestial

rapture.

The thrumming subsided over

the next week. So did Cecilia’s sexual

appetite. Conversation dwindled. Cecilia

had always done most of the talking, mostly about new positions and feats of

sexual agility. John tried to engage

her, but their exchanges consisted of perfunctory discussions of schedules and

grocery lists. Cecilia began to sleep on

the living room couch. Their libidinal torches subsided to a flame,

then a flicker and then nothing. It was

over.

She disappeared in the

fall. Packed up all her clothes and took off without any goodbyes or a note.

Her cell phone was disconnected and when John went to find her at the Natural

History Museum they’d never heard of her. He stayed in her apartment in

case she came back. When the lease was up at the end of the month, he

renewed it.

John was not unhappy to

return to his old life of work and a few close friends. He didn’t miss Cecilia and he didn’t miss the

sex. He assumed that the pheromones had simply dried up and blown away. His friends encouraged him to use an online

dating app, but he wasn’t interested. He didn’t care if people thought

that, as a single man, he was probably gay. He assumed that he was

asexual, or that it took a special woman to torch his libido. If it

happened once, it could happen again. He could wait.

He told his family

things hadn’t worked out. His mother patted his hand and said, “I’m so

glad you’re happy on your own, I mean with your own apartment and all.

You don’t need a looker. They’re more trouble than they’re worth. I’m

glad you got out before it was too late.

You need somebody steadier, someone you can have children with.”

For years he still

found scattered cicadas in the apartment, one wedged deeply in the couch

cushions, one behind the washing machine, another in the toaster tray. He

kept one cicada on his bathroom counter as a memory of his cicada summer. Occasionally he’d get a postcard from

Cecilia, always in the summer around their anniversary, always from a different

place in the United States, always promising to see him again “sometime

soon.” She never included a return address.

One day John noticed a

cicada tapping against his bathroom window.

His hand jerked and he cut himself shaving. Blood dripped down his

neck. He picked up the cicada from the counter and held it up in front of

the mirror next to his face. He shuddered at the similarities – his

bulging eyes, red rimmed from spring allergies. The pattern of his

trickling blood matched the veins in the cicada’s cellophane wings.

“Oh my God,” he

said. “I look like a cicada. I’m a human cicada.”

The phone call finally

came. “Hello John, it’s Cecilia. I’m

back. Are you ready for me? It’s our summer again.” Her tongue

clicked twice.

“Where are you?”

John shook off his long hibernation and reveled in the ancient pulse of the

thrum. #

Follow Liza Blue on:

Share: